Me and My White Privilege

|

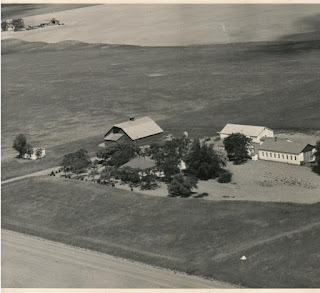

| From Makah Museum photo collection |

Mom was enthralled as the scientist led us to various tents showing us some of the treasures. Mom had a thirst to know more about these people, their lifestyles, and their cultural ways. I cared about getting home and out of the rain.

As a teen, I was too wrapped up in my current life to care much about what life was like before me. You could say I was strong-willed and selfish. Going after my own success defined me. I didn’t have time for an archeological dig, or time to understand a primitive culture that no longer existed. Now I know the term for this: White Privilege. For me, life was all about me.

Worse still, if I had taken a greater interest back then, and kept building on my knowledge of those who’d come before, perhaps the sting that I feel when I hear about White Privilege wouldn’t hurt so much. Mom tried.

I can’t reverse the decisions I made back then, but I can be a better listener to those I need to learn from, and to study like I should have years ago. So, I recently went back to where Mom tried to first interest me. It’s a three-mile hike along a beautiful woodland trail to the Pacific Ocean. Reading from a scientific report as my husband I rested along the ocean shore, I learned that a massive combination of an earthquake/tsunami/mudslide destroyed the Osett Makah Native American community.

|

| Trail to Cape Alava, and the Osett Memorial |

Archaeologists determined that there had been eight post and beam houses—one at least 800 years old that could hold as many as 40 people each. Western red cedar was abundant, durable and pliable and was used as posts and planks for walls. The Makah people were resourceful and even used massive whale bones for retaining walls and as coverings for drainage ditches.

The lead archeologist, Dr. Richard Daugherty left the site with 90% of it untouched. He wanted future scientists and those who desire to learn more from discovering the past to have even more modern technology to do so. Now, it’s all gone back to nature except for a small-scale replica of a Makah longhouse that marks where the village once stood. Within it, are small sacred offerings of whale bones, feathers, and shells—gathered by those who honor the memory of those who lived here. These hard-working people loved this land, cared for it, and as Mom knew, had stories to tell in the things that were left behind.

I was humbled as I read about the ways these brave people faced their hardships. I was ashamed to imagine that I even began to understand their perspective.

As a nation, we’ve had the chance to listen to those who’ve lived here the longest, but in an effort to gain more ground, we’ve lost something even more valuable—our connectedness as fellow humans. White Privilege can take some destructive forms, but for me, not caring about those who first cared for our land is about as privileged as it gets.

I recently heard remarks from an exceeding dedicated and hard-working Alaska Native, Joe Kaaxuxgu Nelson, “The world needs our Indigenous knowledge to help solve problems. As Native communities we’ve always valued relationships with each other, knowledge relationships to the land, to the resources, relationships between generations, relationships between the past, present, and future. It’s an exciting time to keep working together to bring solutions to ensure that our grandchildren have strong and healthy communities to be part of.”

Isn’t that what we all want? Yes. I pledge to be part of the solution as well, and not on the sidelines, or worse, part of the problem—a problem steeped in a privilege I never deserved in the first place.